I’ve been reading Ann Weisgarber’s novel The Personal History of Rachel DuPree (more on that in a separate post). At one point, Rachel notes that her husband Isaac has built the family a wooden house and describes the sod house they lived in before:

Its walls were nothing but squares of sod. The ceilings sagged. The floors were dirt. Summers, grass grew on the inside walls and I’d take a match and burn the shoots to keep the prairie from staking a claim on the inside of our home. (6)

Though I knew no one who lived life on the prairie, I recognize the gesture of burning the shoots to keep the wilderness from taking over. Though my family and many of my friends lived in the kind of community that Mitchell Duneier may have termed a ghetto, I saw people actively working to keep those elements from coming inside.

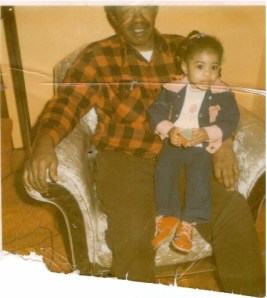

Duneier concludes that the black men at Valois come to the diner because there they can fashion a world that reflects the moral life and character they envision themselves having since the ghettos around them did not. People that I knew and admired made a Valois of their home lives by metaphorically doing as Rachel did. My grandfather used to chastise people who would wash out glasses in the kitchen sink that they had just taken from the cabinet to get a drink. “We ain’t got no roaches here,” he would say. “You ain’t got to wash out no glasses ’round here.” It would be a remark I remember having to think about: Do people who do have roaches in their homes wash out glasses because of the bugs or the spray? Whatever the answer, my grandfather wanted it to be clear that he lived in a clean environment. He was proud of this cleanliness.

That there were never any dirty dishes in our kitchen sink was something my father mentioned to me. He noted this when he would reminisce about the things that were attractive to him about my mother and her family: the house was always clean.

Outside we always had a well-maintained lawn, a flower bed that grew hydrangea, a trellis where the most beautiful african violets climbed, and a garden in the backyard where we grew tomatoes, cucumber, peppers, and collard greens; so did our neighbors.

I’m not clear on where these people are in the lives of the black men who frequent Valois or what accounts for the difference between people who make their home environments what they want and those who find environments like the one’s they want at home. Duneier suggests that for some of the men, they lived in depressed buildings that would have conspired against personal attempts to control them. For example, in Chapter 2, he writes about Jackson’s problems with the landlord of the building he and Duneier shared:

Our studios were in a terrible state of disrepair. The first time I went over to Jackson’s place was when, knowing I had a camera, he asked if I would take photographs of his apartment so that he could use them as evidence if he ever decided to sue. Paint was chipping and peeling on all four walls and flaking down from the ceiling. The stove didn’t work. The wall beneath his window hadn’t been properly insulated. The bathroom light socket had come out of its fixture and dangled on a wire a few feet above the bathtub. (27)

Jackson’s apartment bears witness to the disregard shown to the poor.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately as I’ve considered why people find ambition so attractive. While I value being motivated toward becoming a better person, I don’t include having power and status among those meaningful ambitions. Interestingly, a young woman recently asked me to help her with a school project about this subject. Though this is not the exact prompt, I was asked to provide her with commentary on what I admired about women who held power and status. Here’s my response:

Well, I don’t admire “status,” if by that you mean authority. If anything, I admire women who have a strong sense of their value without having public, sanctioned, or recognized authority. As you have indicated, there are multiple, compelling, and nuanced ways of having an impact on others. I tend to admire those women who do not try to enforce their impact and assume another’s need for their guidance and vision; in other words, those who do not attempt to make children of others. Take my friend Tanya as an example. It never occurs to Tanya to assume rank in someone else’s life. She enters into relationships with an understanding that she is entering into community with another and not that her job is to assume that she will guide and influence their behavior. Now of course there are situations where someone has authority or is in authority but that role has boundaries.

Since I have been re-reading A’Leila Bundles‘ wonderful biography of her great-great-grandmother Madam C.J. Walker entitled On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker, I’ve considered my own ambivalence about money and career ambitions. It makes sense for a woman who had worked very hard as a farm laborer and a laundress to desire greater control over her own labor and her life. It would also make sense that someone who had experienced the indignities of segregation and who had witnessed the grisly spectacle of the aftermath of lynching to have wanted a commanding voice. In one astounding passage from the biography, Bundles cites a black Mississippian who commented on the conditions black folk left behind when they quit the South:

“After the summer crops were all in, any of the white people could send for a Negro woman to come and do the family washing at 75 cents to $1.00 a day […] If she sent word she could not come she had to send an excuse why…They were never allowed to stay at home as long as they were able to go.”

The expectation that black women would provide an excuse for not satisfying a request to work speaks to my rejection of “power” and “status” that turns others into children. Walker’s historical significance has a great deal to do with the opportunities she created for those black women to work under their own power.

What gets me, though, is the way that materialism creeps into stories like Walker’s in ways that raise questions regarding uniqueness of vision and voice. For example, when Bundles writes about Fairy Mae, Walker’s adopted grand-daughter being seduced by the environment surrounding her new family, she notes this:

Fairy Mae understandably was seduced by the opulence of Madam Walker’s Indianapolis home with its twelve lavishly furnished rooms. For a child accustomed to living with several siblings in less than half the space, the calm and quiet of the rose-and-gold drawing room–with its brilliantly patterned Oriental rugs, gold-leaf curious cabinet and Tiffany chandelier–was like paradise. In the library, Fairy Mae could hold soft leather-bound books, run her fingers across the gleaming keys of the Chickering baby grand piano and admire the lovely oil paintings of young William Edouard Scott, the local colored artist who had studied in Paris. On a table covered with Battenberg lace, she watched Madam Walker’s guests being served dinner on Havilland china with monogrammed silverware with sparking crystal goblets. (143)

Certainly, I see this moment as serving a few purposes for the writer: 1.) explaining Fairy Mae’s desire to remain in this environment, 2.) documenting Walker’s furnishings and appointments. But what I am most interested in is the kind of work such documentation performs relating to cultural presumptions. That is to say, even without being told, the reader is supposed to think that these trappings mean that Walker lived in a very nice home. We’re supposed to think that the rational thing to do with money is to spend it on the best things that it can buy. I don’t know.

I’m not sure that I’m convinced of what makes some material object best. I know what some might say but I’m not sure I agree. For example, it doesn’t matter what kind of china Kris Kardashian served Thanksgiving dinner on, I prefer my Food Network collection plates to it and the dinner conversation I was able to manage over the food. And though the lamp in my son’s room isn’t made by Tiffany, I don’t think he notices when we read to him at night. Again, I understand Bundles’ point, especially at the juncture in the text at which she made it. I just wonder about having “the best” things that money can buy and the presumptions about the lives that go along with them. (I also question the notion that this performs some kind of important historical work.)

Duneier ends his chapter “A Higher Self” noting the importance of claiming a present self that reflects notions of a prior self. He contends that the black men at Valois have a memory of themselves living out the values that their present environment makes nearly impossible for them to execute. Valois gives them a place to live out these remembrances. If this is their motivation for coming to Valois, it offers a wonderful model by which to live. Pursuing a “higher self” has nothing to do with designer labels, but everything to do with conversation, listening, and sharing; it involves compassion and reflection. Burning the shoots serves as an attempt to keep the present from taking over the past or of maintaining the good of the past recreated in the present.

It makes sense that people would want to materialize all of the good they see in themselves. The articulation of this desire dominating our current moment involves the representation of this desire through materialism alone. What the men at Slim’s table reveal is that it is possible to see one’s higher self through camaraderie and fellowship if not through one’s address.

I also think keeping up with the Jones’s might have gotten a bad rap because of our attenuated focus on its association with material possessions. But trying to keep up with people who plan healthy meals for their family, who are organized, or who have beautiful gardens is not a bad idea. The documentary film A Man Named Pearl offers a wonderful example of this. The film focuses on the beautiful topiary gardens of Pearl Fryar. Fryar’s own yard offers a visual feast for visitors from his home state of South Carolina as well as for interested observers around the globe. Interestingly, he has inspired his neighbors to create their own topiary gardens. Their work is also on display in the film and they offer testimony concerning Fryar’s influence on them and their efforts to keep up with him. Fryar enjoys helping his neighbors to develop their topiary and they in turn welcome his support. In this instance, keeping up is cooperative rather than competitive.

I also think keeping up with the Jones’s might have gotten a bad rap because of our attenuated focus on its association with material possessions. But trying to keep up with people who plan healthy meals for their family, who are organized, or who have beautiful gardens is not a bad idea. The documentary film A Man Named Pearl offers a wonderful example of this. The film focuses on the beautiful topiary gardens of Pearl Fryar. Fryar’s own yard offers a visual feast for visitors from his home state of South Carolina as well as for interested observers around the globe. Interestingly, he has inspired his neighbors to create their own topiary gardens. Their work is also on display in the film and they offer testimony concerning Fryar’s influence on them and their efforts to keep up with him. Fryar enjoys helping his neighbors to develop their topiary and they in turn welcome his support. In this instance, keeping up is cooperative rather than competitive.